If you have been around the anime and manga community for any amount of time, you have probably heard of shojo manga. This genre of the medium typically stars a female lead and are more character driven. Shojo manga has elements of drama, romance, comedy and sometimes action. The art styles are typically stylized to look very pretty, and contain lots of sparkles and screen tone backgrounds, along with adorable characters with large eyes and contains more of an emphasis on fashion and costume design that other genres of manga. Now let’s dig a little deeper, into one of the sub genres of shojo manga. Mahou shojo, or magical girl manga as it is referred to in the English speaking parts of the world, expands on the conventions of shojo manga, and introduces some of its own elements to carve its own niche in the vast, ever-expanding world of manga. The genre usually consists of young girls that have some sort of magical ability bestowed to them, be it through a talking animal companion, a deity, an angel or some other sort of being. The genre also makes use of talking animals and animal-like companions that serve as guides on the heroine’s quest, as well as a cute mascot for the series. The same elements of shojo manga are present, but these additions of magic, some sort of mission or goal that requires use of said magic, and talking animals friends are common tropes that exist in the magical girl niche of shojo manga. So without further ado, let’s take a deep dive and examine the history of the genre, some of its typical tropes and settings, and what makes this genre special. Grab your magic compact, put on your battle outfit, and I will be your magical animal companion on this expedition into the realm of magical girl manga.

The manga that can be traced back through the lineage of magical girl franchises is Himitsu no Akko-chan/The Secrets of Akko-chan in 1962, but before we jump into that, I would like to examine a potential inspiration for the genre, or “proto-magical girl”; this series being Osamu Tezuka’s 1953 manga, Princess Knight. Princess Knight’s protagonist, Sapphire, possesses two hearts, one is a blue and one is pink, representing both male and female souls. The story takes place in a medieval European setting and follows Sapphire’s adventures as she has to hide her identity to ascend to the throne of her kingdom, as a woman is not eligible to do so in their land. This is made easy by the boy heart inside of her. Things get complicated for her when an angel named Tink is sent to retrieve Sapphire’s male heart, as well as a duke that is vying to put his son on the throne that would repress the people of their land. While Princess Knight does not feature any magic in the sense of how we think of the magical girl genre now, it does introduce a few key cornerstones of the genre, transformations, a whimsical, magical world and a strong female lead. While these transformations aren’t like what magical girl transformations are now, the use of giving Sapphire two hearts that let her do an action outside of what a normal human can do is essentially the idea of the magical girl transformation in its most simplified state. The whimsical, charming narrative and the strong female protagonist are, however, two things that magical girl manga still possess to this day, in the same fashion as Princess Knight did them.

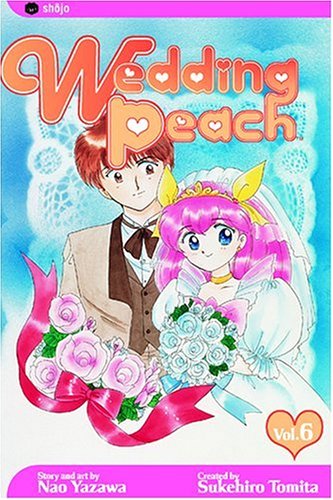

After acknowledging the blueprints of the genre contained in Princess Knight, we are now able to examine The Secrets of Akko-chan, the first manga that ticks every box required to be a magical girl manga. This pioneering manga of the magical girl genre ran from 1962 to 1965 in Shueisha’s Ribon magazine, which dates the official first entry in the genre nine whole years after the first pages of Princess Knight were published. The story follows an elementary school girl named Atsuko Kagami, who has a strong love of mirrors. After her treasured favorite mirror ends up broken, Atsuko chooses to bury it in the ground, akin to a funeral, as opposed to just toss it in the garbage. She is then approached in a dream by a spirit called The Queen of the Mirror kingdom, who is moved that Atsuko would treat the broken mirror with such respect, and in return, gives her a magical mirror and teaches her spells that allow her to transform into anything she desires to. This series is of monumental importance to the genre for a some key reasons. First, it is the first series to utilize traditional magical girl transformations, setting the standard and introducing the trope to the genre. Another is the charming way that the story is portrayed, in both its narrative and through the use of shojo-stylized illustration. Another neat fact is that in the 1969 anime adeptation of the series, Atsuko’s transformation is done via the use of a compact mirror, which is something that titans of the genre, such as Sailor Moon and Wedding Peach, would go on to incorporate into their stories as their transformation item of choice.

At this time, the term “magical girl” had not yet been coined, and the term “Majokko”, or Little Witch in English, was used to describe the genre, due to the success of many series throughout the 60’s and 70’s having a main character that fit the description of a little witch. Stories such as 1966’s Sally the Witch manga, and anime series’ such as Mahoutsukai Chappy and Majokko Megu-chan in 1972 and 1974 respectively. While The Secret of Akko-chan was the first magical girl manga, the series was not actually the first animated magical girl series. Sally the Witch’s anime adaptation was handled by Toei animation only months after its manga debut, predating the animated adaptation of The Secret of Akko-chan that would not be aired until 1969. Majokko anime and manga were more in line thematically with the American magic sitcom Bewitched than the mystical superheroes that the genre would later lean into. Majokko franchises had tropes such as hiding your powers from a majority of people and using magic for comedy, and also added themes such as the bonds of friendship and kindness. Magical girl manga in this period was the progenitor of having strong character dynamics and deep friendships between the main cast. Majokko Megu-chan has been especially praised for its use of multiple magical girls, and the bonds of friendship that form between them, making it a cornerstone series to the genre for cementing the idea of having a charming dynamic between its character that is engaging to follow.

Toei animation was also instrumental in the rise of the majokko/magical girl genre, creating an adaptation of The Secret of Akko-chan, as well as animating original magical girl works throughout the 70’s. They were responsible for Majokko Megu-chan and Mahoutsukai Chappy, as well as the adaptation of another series that would expand the genre into a more shonen direction and abandon the cute, enchanting majokko style for a more action oriented approach. This series is Go Nagai’s Cutie Honey, which ran in Akita Shoten in Japan from 1973 to 1974. Go Nagai was previously known for the occult horror-action series Devilman, and took some of the more mature themes of his narrative and art style and applied them to Cutie Honey. The story follows Honey Kisaragi, a sixteen year old girl attending Saint Chapel School for Girls. When her father is murdered by an organization known as Panther Claw, Honey gets involved in a conflict against the organization, which leads her to find out she is an android that can transform into the red-haired fighter, Cutie Honey. Cutie Honey is another series that is monumental in its influence on the genre, being a major influence on series that would come later, such as Sailor Moon, Wedding Peach and Pretty Cure. The direction the series took in tone and narrative would be the standard for the magical girl boom of the 1990’s and 2000’s. The series took the existing transformation and alternate identity tropes and gave them their own flavor. Cutie Honey is also credited as being the first female protagonist of a shonen manga, and was the first magical girl series to bridge the gap between shonen and shojo demographics, leading to its rise to popularity and cross appeal between fans of the two. The series has also spawned many spin-offs and alternate retellings of the original manga, written by Go Nagai, but having a different illustrator; these include 1992’s Cutie Honey 90’s, 2003’s Cutie Honey a Go Go, and the most recent installment, Cutie Honey SEED, which ran from 2004 to 2006.

As we move into the 1980’s, we see the term “magical girl” replace the majokko title for the genre. This is change is prompted by Toei Animations 1980 series titled Lalabel, The Magical Girl. Lalabel, The Magical Girl follows the titular hero, Lalabel as she lives her life in a world of magic, until a plump plunderer named Biscus starts stealing the magical objects of their world. In an altercation, Biscus transfers both of them to the human world, where she chooses to stay with a foster family until she puts an end to Biscus’s mischievous deeds. In addition to the srtruggle between Lalabel and Biscus, the story also explores Lalabel’s interactions with the unfamiliar world of humans, and shows her develop a liking for it as the series progresses. This series continued the tradition of established magical girl conventions, and while being a more wholesome series, had sprinkles of action in it as well. The 1980’s also brought with it more studios throwing their hats into the magical girl ring, with Ashi Productions releasing the anime Magical Princess Minky Momo in 1982, and Studio Pierrot giving us Creamy Mami, The Magic Angel in 1983. These two series, as with Lalabel, not only solidified existing tropes, but introduced ideas that would both influence the magical girl craze of the following decade, as well as in the case of Creamy Mami, giving the genre its lovable talking familiars in the form of cats that gift the protagonist their abilities. Magical girl franchises and talking animal and cute creature familiars are one of the most iconic tropes in anime and manga, and this decade is where that idea really comes into full force. Minky Momo would go on to receive a multitude of OVA over the years, and finally a manga in 2004, which is the latest adaptation of the series, while Creamy Mami would get a manga version of the story the same year the anime debuted. During this decade, the influence of magical girl anime and manga starts to find its way into other genres as well. One such high profile example of this is Kosuke Fujishima’s 1988 smash hit, Oh My Goddess!. While the series cannot be considered a magical girl manga, due to the main character, Keiichi Morisato, being a college-age male, the romantic comedy series does make use of many of the genre’s standard conventions. Keiichi finds himself dialing the wrong number when trying to order Chinese food, and ends up calling The Goddess Helpline, which leads to the goddess Belldandy appearing before him and offering Keiichi a wish, to which he replies that he wishes a goddess like her would stay by his side forever. This begins Keiichi and Belldandy’s cohabitation, and the story from then out follows the daily lives of the two. Eventually more goddesses, Belldandy’s sisters Urd and Skuld come to live with Keiichi, and they must hide their magical abilities from the rest of the population. The series makes use of magic as a form of comedy and character development, which is something the magical girl genre has been known for since The Secret of Akko-chan in 1962. The wholesome, charming tone of the series also reflects those of the early magical girl pioneers. Later in the series, magical battles between the goddesses and the forces of hell come into play. While magical girl franchises have had battles and action in them as early is Cutie Honey, this common association would not be fully cemented as a foundation of the genre until the early 1990’s, making Oh My Goddess! ahead of its time in that respect. As previously noted, the series does not feature a female lead as the primary protagonist, disqualifying itself from donning the magical girl genre label. Another deviation in the series is that there are no transformation sequences. The goddesses are always in their goddess form and have no need to transform into magical beings when magic is needed in a situation. Despite these differences, the magical girl influence on the series is undeniable. This is important for the genre in that it shows the cultural significance that the genre has, as its tropes, plot devices and themes are now being utilized by franchises outside of the realm of magical girl and majokko series. The magical girl genre is long established at this point, with millions of fans in Japan and abroad (for the few people able to obtain anime and manga outside of Japan at this point in time, as localization was not widespread yet), what would happen in the next few years would catapult the genre to new heights, and change the face of the genre forever.

At the turn of the decade, there is a calm before the storm. Nami Akimoto’s 1991 magical girl manga, Miracle Girls follows two twins, Mikage and Tomomi Matsunaga with the ability to swap locations with one another and communicate remotely via telepathy. This series continued the trend of the traditional 1980’s magical girl manga into the 1990’s, and was the last manga of that era that followed those stylings (though in the later half of the 90’s and 2000’s, series would take influence from this school of magical girl manga) before the boom and revolutions to the genre that would come just months later. Enter Sailor Moon; in late 1991, Naoko Takeuchi gave the magical girl genre a new direction, making her manga about a group of female warriors that protect the earth from threats that come from beyond earth. Instead of taking cues from the majokko genre or past magical girl series’ Sailor Moon opted for a more action driven approach, not unlike what we saw with Cutie Honey, but drew in influence from other sources as well, such as Kamen Rider, Super Sentai and Saint Seiya. Sailor Moon follows Usagi Tsukino, a young schoolgirl who is approached one day by a talking cat named Luna, claiming Usagi is the soldier of love and justice, Sailor Moon. She is given a magical compact (a trope of the genre solidified by the 1969 The Secret of Akko-chan anime adaptation) that transforms her into Sailor Moon, and defends the earth from the evil Queen Beryl, as well as gathers other warriors to aid her in battles. While Sailor Moon plays off a lot of the existing magical girl tropes, such as the aforementioned compact as a magical object from Akko-chan, the strong dynamic between the girls of Majokko Megu-chan, and the action-oriented approach to conflict of Cutie Honey, they mixed all of these aspects with influences from shonen battle manga and live action tokusatsu shows to create a unique magical girl experience. The manga ran in the shojo anthology Nakayoshi from 1991 to 1997, and received an anime adaptation from the queen of magical girl studios, Toei Animation, the following year that launched the series’, as well as the genre’s popularity to new heights. This new blood into the magical girl formula would give life to many other series that would throw their hats in the ring with their own take on the magical girl battle teams. Throughout the 1990’s, you had Wedding Peach, Saint Tail, Magic Knight Rayearth, Cardcaptor Sakura, Cutie Honey Flash, Phantom Thief Jeanne, Corrector Yui and the Tenchi Muyo spin-off, Magical Girl Pretty Sammy all give their own unique take on the direction the genre had taken since the boon in popularity from Sailor Moon. With the main inspiration for all of these series being Sailor Moon undoubtedly, they all also incorporated various elements of majokko and pre-Sailor Moon magical girl manga as well, making each of them stellar experiences for any magical girl fan. This major gain in popularity, as well as many new series embracing this new approach to the magical girl formula, lead to the genre being one of the premier subgenres of shojo manga, something the magical girl scene would be able to hold onto well into the 2000’s. There were also magical girl adjacent franchises, such as Revolutionary Girl Utena and Mamotte Shugogetten, which while not having enough criterion to meet the standard for a magical girl series, were heavily inspired by the genre and other similar genres. Revolutionary Girl Utena draws strongly from Princess Knight, the series considered the grandmother of the genre, while Mamotte Shugogetten is very Oh My Goddess inspired.

Our journey back to the golden age of magical girl manga would be incomplete without addressing the other titan of the time, the all-female manga collective CLAMP. While not exclusively a magical girl manga team, the collective is responsible for two of the most recognizable franchises in the genre, Magic Knight Rayearth and Cardcaptor Sakura. Magic Knight Rayearth has a very medieval fantasy setting, inspired by Tolkien and Dungeon and Dragons, and follows three students from different schools that take a field trip with their respective schools to Tokyo Tower on the same day. The girls, Umi, Hikaru and Fuu, are then transported to a fantasy world known as Cephiro and are tasked with saving the world and its princess, Princess Emeraude. This swords and sorcery setting is significant in it being a radically different setting than the traditional contemporary urban fantasy backdrop that most magical girl stories make use of. Cardcaptor Sakura was CLAMP’s other big magical girl series, and unarguably their most recognizable work. Cardcaptor Sakura follows Sakura Kinomoto, as she finds a mysterious deck of cards stored in her family’s home and accidentally releases them from their seal, scattering them across Japan. Along with the cards awakening, the guardian of their seal, Kero is also awakened, and tasks Sakura with gathering all of the cards. Each card has its own magical properties and is able to be used by the owner to draw out the power of each card. Cardcaptor Sakura has become a cornerstone of the genre and one of the magical girl genre’s most beloved works. The series has since spawned a multitude of adaptations, including a sequel manga that was introduced in 2016, much to the delight of magical girl fans across the globe. The series’ protagonist, Sakura Kinomoto, along with Sailor Moon’s Usagi Tsukino, would become the new faces of the genre, and to this day are still the most identifiable icons of not only this generation’s magical girls, but of the entire genre.

The 2000’s magical girl landscape is twofold; what I would consider the golden age of the genre is still in full swing at the turn of the millennium, but there are also some seeds planted around the mid 2000’s that would signify a radical change in the direction the genre’s mainstream would go for a brief period the following decade. The early 2000’s is part of this golden age and boom brought on by the successes of Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura, as evidenced by the success of Tokyo Mew Mew in 2000. The series is largely influenced by the big names of the 1990’s, but also isn’t shy about letting its own personality be on full display. The story follows Ichigo Momomiya, and after an event leaves her with half-human half-wildcat DNA, she becomes involved with something called “The Mew Project”, where Ichigo finds there are other girls with the same hybrid DNA as herself, and they are given the mission to guard the planet from aliens that harness the power of earth’s animals and use them to attack humans to further their goals. Around this time, America was just as in the middle of this boom as the genre’s native Japan. While Sailor Moon found her way stateside in the latter half of the 90’s, beloved works that had released in Japan at that time were just now having their stories translated and their animated counterparts dubbed in English, making the magical girl craze a phenomenon that resonated across the globe. Cardcaptor Sakura and Tokyo Mew Mew graced American TV sets with dubbed versions of their anime in the early 2000’s, along with many other recognizable names getting licensed for manga and DVD releases in the Western Hemisphere. Another monumental series of the 2000’s is the magical girl institution that is Pretty Cure. This titan of the anime and manga world has spawned eighteen different animated series’ with many of them receiving manga counterparts as well, something that is typically reversed, with the manga usually being the original source. Many of the Pretty Cure stories are self contained, but follow similar motifs and share many common themes and references to past incarnations of the metaseries. Each iteration has its own cast of teenage characters that are gifted abilities by fairies to become magical warriors. These magical warriors are almost always tasked with defending earth from malicious forces that wish to endanger the planet and bring misery to its citizens. Futari wa Pretty Cure, the first of many, debuted in 2005, and follows Nagisa and Honoka and their battles against the Dark King and his forces. Another important series in the genre that released in 2005 was the manga Shugo Chara. Written and illustrated by the mangaka duo known as Peach-Pit, Shugo Chara draws influence from the Majokko school of magical girls and combines it with a similar feel and energy to Cardcaptor Sakura. The story begins with ten year old Amu Hinamori, a girl who appears cool and likable to her classmates, but deep down wants to find out who she really is inside. She shows resolve to find her true self, and the next day, she wakes up with three eggs with colorful playing card symbols on them in her bed. These eggs hatch and become guardian characters, small beings that represent Amu’s personality and allow her to change form into a self she would like to be. She finds out there are others at her school with guardian characters, and friendships and a secret club are formed. As the story goes on, an evil music corporation gets introduced to the plot looking for a specific guardian character egg that is said to grant a wish, and this leads the story to move in a more action oriented direction, while maintaining the elements of self-discovery and the strong bonds between the characters a focus throughout the story. The strong bonds of the characters and the early story has a subtle Majokko Megu-chan influence to it, but incorporates that idea stronger than the other magical girl stories going on at the time. The series also gave birth to many spin off manga and anime, such as the sequel manga, Shugo Chara Encore, and two additional anime series after the initial animated adaptation aired. Kodansha comics was the distributor for the manga in North America, and released all twelve volumes of the story between 2007 and 2011. On a more personal note, the series is responsible for getting me into the magical girl genre, I remember getting the manga from our local library as a kid when it was new, and from there, it fostered a love of the genre within me, and I am glad Shugo Chara has its place in the magical girl canon.

Before we jump to the next decade, I had mentioned the seeds of a change in direction being planted around this time. This germination of a darker, edgier direction for the genre has its roots in Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha. The series wears much more of the shonen battle influence on its sleeve, and contains battles and themes such as a focus on the strength of powers and abilities, making it something akin to the Dragon Ball Z of the magical girl world. This more battle oriented tone aimed at a largely male demographic sets the stage for tone of what was to come in the following few years.

While Nanoha opened the gates to this form of magical girl, the darker tones and subversion of many traditional magical girl tropes was on full display in Puella Magi Madoka Magica. The series debuted on Japanese late night television in 2011, and soon found itself with movies, a manga adaptation and multiple manga spin-offs. The premise is that an alien creature named Kyubey promises to grant a wish to young girls in exchange for their cooperation in fighting witches. Protagonists Madoka Kaname and Sayaka Miki find themselves involved in a sinister situation when they get involved with Kyubey, and meet other girls who had accepted his terms. The series takes the genre into a much darker direction, dealing with themes of the cost of obtaining power, death and deception. The series would also give life to imitators that continued the trend of darker-themed magical girl plots, such as Magical Girl Site, Magical Girl Apocalypse and Yuki Yuna is a Hero. While this trend was all the rage in the early and mid 2010’s, it has slowly been dying down, with prominent series in that subsection of the genre like Magical Girl Apocalypse ending in 2017 and its spin-off, Magical Girl Site ending in 2019. While seemingly revolutionary for the genre, bringing in tourists from a primarily shonen and seinin readership, the torch of the contemporary dark fantasy trend is really only carried on by the new Madoka Magica spin-offs and movies and the vast wealth of Yuki Yuna is a Hero properties, such as video games, a ton of different manga series, and multiple anime seasons.

During this time, what happened to the traditional magical girl formula? While in the early 2010’s, not many new series were being made and others found themselves wrapping their stories up, the genre had a revitalization in the announcement of Sailor Moon Crystal. This adaptation, handled by Toei Animation, was more faithful to the original manga, cutting out the filler of the first anime series and focusing more on Naoko Takeuchi’s original manga story. So far, of the five major story arcs present in the manga, four have been adapted, with the latest, the Dead Moon Circus arc coming to us in the form of two movies that were released early 2021. In 2016, the other queen of the genre came to return to her rightful throne. Sakura Kinomoto returns to us in the long-awaited sequel to Cardcaptor Sakura in Cardcaptor Sakura: Clear Card. The story finds us later in the furure, with Sakura and Syaoran Li now in junior high. When Sakura’s clow cards turn blank and are left with no magical properties, her and Li make it a point to discover what has caused this, and how to regain the power of the cards. As of right now, the series has 11 volumes and is still going strong. Cardcaptor Sakura: Clear Card has also received an OVA and a 22-episode anime series since its debut. Another series that was on my radar at the time that sadly didn’t gain much traction was xx Demo Mahou Shoujo ni Naremasu ka?(Can You Even Become a Magical Girl?). This series, while faithful to the magical girl tradition before it, features an eighty-eight year old woman, Ume, as the protagonist, and sees her transform into her younger self when she transforms to fight the villains of the series. Ume’s granddaughter Momo is obsessed with magical girls and is a huge fan, even idolizing Ume’s magical girl form, without realizing that it is in fact her grandmother. Ume protects her town from demons that are hell bent on creating pain in people’s hearts. The story is a fun read that encapsulates what makes the genre so enchanting and any fan of the genre would love what its pages contain.

With all of this rich history of the genre, the question becomes, where is the genre headed next? With the return of Sailor Moon, Cardcaptor Sakura, and a new Tokyo Mew Mew anime announced, will we see a renaissance or a second golden age of the genre? Will the grittier, contemporary dark fantasy take on the genre return to cultural relevance? Will we see new life breathed into the majokko origins of the genre for a new generation of fans? Will a new series take the genre in a new direction without compromising its roots, similar to what happened in the 1990’s? I personally don’t see the genre reaching the heights of its peak again for a long time, but I do think the genre has received a lot of love and attention as of late with all of these prominent figures in the genre coming back to provide us fans some quality entertainment. This rising interest in the genre could quite possibly give incentive to new creators to grace the world with new, original magical girl stories. Whatever is in store for the genre, only the future knows; or a talking cat from the moon that is from the future. If any of you out there find one, don’t spoil the fun for the rest of us!